ANATOMY OF A JELLYFISH

Jellyfish are animals! They have been on Earth for more than 500 million years and were some of the first animals. They can be found throughout the world’s oceans, from shallow waters down to the deep sea, and in a wide range of temperatures and salinities. Jellyfish are named for the soft composition of their bodies, which are composed of about 95-99% water! This is one of the characteristics that allows them to live in such a wide range of conditions. All jellyfish are in the phylum Cnidaria (pronounced “nih-DARE-ee-uh”), named for the Greek word for stinging nettle. There are thousands of species of Cnidarians, which also include corals and sea anemones, and over 200 species of “true jellyfish,” or those belonging to the class Scyphozoa (pronounced “sai-fuh-ZOW-uh”).

These animals all share a basic body plan and life history. In addition to the Scyphozoans, many other species are often grouped with jellyfish, including other Cnidarians in the class Hydrozoa (pronounced “hai-druh-ZOW-uh”), such as the Portuguese man o’ war, and those in the phylum Ctenophora (pronounced “ten-AH-fuh-ruh”), or comb jellies. While these animals are not considered “true jellyfish,” they share physical and behavioral traits.

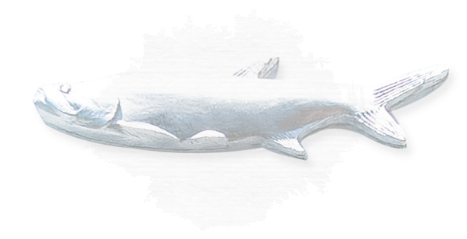

The familiar umbrella shape of true jellyfish is formed by the bell. This consists of an outer membrane (ectodermis) and inner membrane (gastrodermis) with a jelly-like layer in between (mesoglia). Jellyfish are very simple animals; they have no brain, heart, or any other organs. They have a gastric cavity with only one opening that is used for feeding, reproduction, and respiration. They do not have any blood or circulatory system; molecules move in and out through simple diffusion directly across the different membranes. Water is moved through the jellyfish through a gastrovascular canal system, moving from the gastric cavity through the radial and ring canals and back again. Tentacles line the edges of the bell; they can be short or trail for many feet. The mouth is surrounded by oral arms, ribbon-like projections that transport food to the mouth.

WHAT DO JELLYFISH EAT?

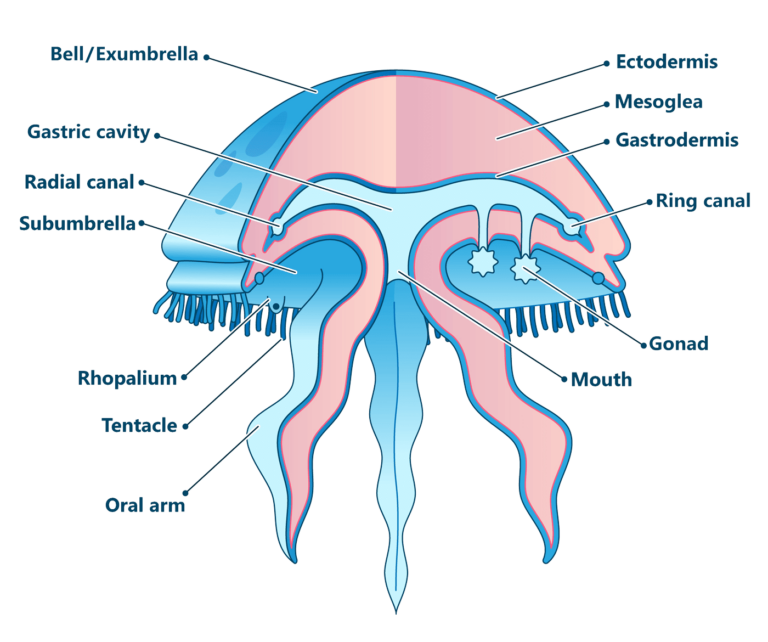

Jellyfish are predatory, they capture and eat other organisms ranging in size from tiny zooplankton to larger prey like fish. Jellyfish also commonly eat each other! Prey is captured in their tentacles and oral arms, which are lined with stinging cells called cnidocytes. The cnidocytes house nematocysts, organelles that have a venomous harpoon that shoots out of the cell when triggered by touch or chemical cues. These activate extremely quickly, only taking about 700 nanoseconds to deploy! The venom is injected into prey, which gets captured in the tentacles and oral arms, then moved to the mouth. The potency of the venom varies by species, as does its effects on humans. There are many jellyfish that are considered harmless to people. However, as anyone unfortunate enough to be stung by one of these creatures knows, there are some with extremely painful stings.

CNIDOCYTE

Some jellyfish, like the Cassiopea, or upside-down jellyfish, have photosynthetic zooxanthellae as well. The jellyfish house the single celled algae in their tissues where it performs photosynthesis and produces sugars using energy from sunlight. This is a strategy shared by many corals, the cnidarian cousins of jellyfish!

WHAT CAN A JELLYFISH SENSE?

Although jellyfish do not have a brain, they are not totally without sensory awareness. Rather than a centralized nervous system, they have a neural net that sends and receives stimulus information. The rhopalia on the edges of the bell are the sensory centers, taking in information about currents/water movement, chemicals, and even balance/position. Different species of jellyfish have varying numbers of eyespots next to the rhopalia that sense light. Many species of jellyfish are phototaxic, or attracted to light. The eyespots and other sensory information from the rhopalia determine the movements and behaviors of jellyfish. A pacemaker near the rhopalia takes in all the sensory information and controls the pulse rate of the bell. When something unusual is sensed around the jellyfish, the pacemaker speeds up the pulses to hopefully move the jellyfish away from danger.

HOW DO JELLYFISH REPRODUCE?

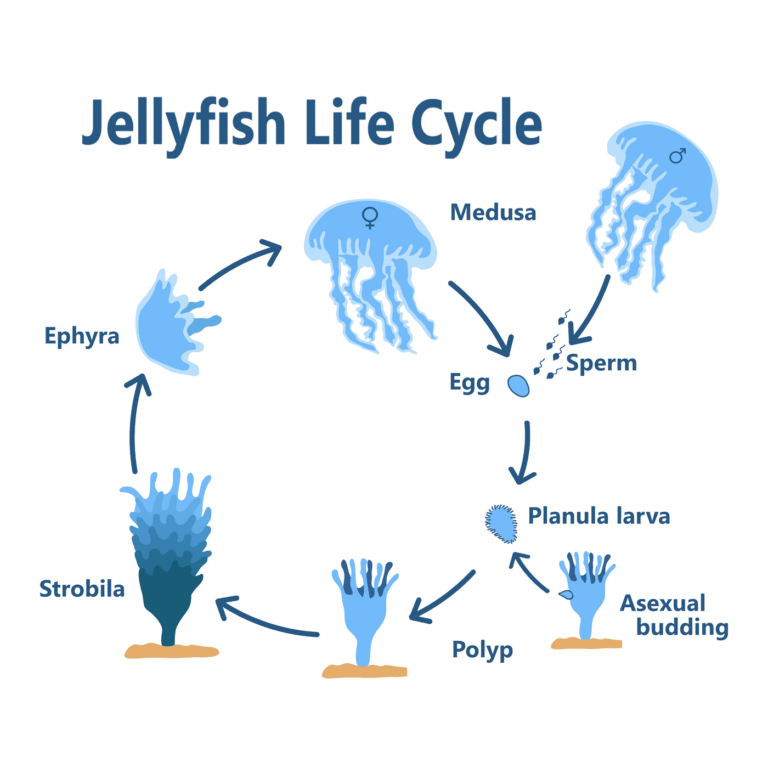

Jellyfish have a fascinating life cycle! They go through two different body plans, the polyp and the medusa. The medusa is the form that we are most familiar with; it is the free swimming adult stage. Jellyfish in this stage are typically dioecious, meaning either male or female, and reproduce by releasing sperm and eggs into the water. There are a few species that practice internal fertilization through the gastric cavity, such as the upside-down jellyfish, Cassiopea xamachana.

Males release sperm into the water where it is collected on the tentacles of a female and transferred through the mouth to the eggs. The eggs are fertilized and then released back into the water as free swimming planula larvae. The larvae use chemical and physical cues to find a place to settle. Once they are in a favorable location, they attach to the surface and develop into a polyp called a scyphistoma. The polyp is much like an anemone, the cnidarian cousin of jellyfish. The polyp has a mouth and is able to capture food from the water column with its tentacles. The polyp can also reproduce asexually by budding. The buds develop on the stalk of the polyp and are released as planula larvae clones. Additional chemical and physical cues, such as temperature changes, trigger the polyp to continue developing and go through a process called strobilation. The head of the polyp splits into 10-15 segments stacked on top of each other. Each segment develops into an immature jellyfish, called an ephyra, which separates from the strobila. The now free swimming ephyra grows into the adult medusa jellyfish. The ability to switch between sexual and asexual reproduction gives the jellyfish an advantage in different environmental conditions.

HOW DO JELLYFISH MOVE?

Jellyfish move using muscular contractions of the bell. These pulses create areas of high and low water pressure that propel the jellyfish. They are not very strong swimmers, but they are extremely energy efficient. In fact, research has shown that jellyfish use 48% less oxygen to move than any other swimming animal! As jellyfish move up and down the water column following prey, they pull water with them. The huge number of jellyfish and other small animals that follow these paths contribute significantly to the mixing of water in the ocean. The cooler, heavier water from deeper in the water column is pulled up and mixes with the lighter, warmer water closer to the surface. This distributes nutrients, heat, and gasses to different parts of the ocean.

While jellyfish have some control over their movements, they are still largely at the mercy of water currents around them. Weather events such as storms and strong winds can cause jellyfish to become concentrated in the same areas or to be washed up on the shore. It is common to find many stranded jellyfish on the beach after these events.

HOW DO YOU TREAT A JELLYFISH STING?

Jellyfish stings, and those from other venomous animals can be very painful and ruin a day in the water. Some may even cause life-threatening allergic reactions and require immediate medical intervention. Fortunately, Florida does not have many creatures that cause severe stings, but there are a few that people should steer clear of. The Portuguese man o’ war, moon jellyfish and Cassiopea jellyfish can all cause an uncomfortable, if not very painful sting. Wearing a rash guard when swimming and watching out for washed up jellyfish on the beach can help prevent stings. There are many folk remedies and lots of conflicting advice on how to treat jellyfish stings, and unfortunately some of these treatments can actually make the stings worse.

Here are a few DO’s and DON’Ts for marine stings from the Florida Department of Health and research about treatment strategies published in the journal Toxins.

DO

Leave the water immediately if stung.

Call the Florida Poison Information Center Network at 1-800-222-1222 or 911 if you begin to have trouble breathing, feel faint or have chest pain.

Douse the area with vinegar, to rinse away the tentacles and deactivate the stinging cells.

If you do this first, you won’t spread the sting to other areas when you attempt to remove the tentacles.

Pluck off the tentacles with tweezers.

Avoid touching the area with bare hands and use tweezers to remove any tentacles stuck to skin.

Apply heat to break down the venom and permanently deactivate it.

Cold may temporarily relieve discomfort, but it may also preserve venom in the skin, and pressure from applying a cold pack can push the venom further into tissues.

DON’T

Don’t scrape tentacles off or rub with sand.

This triggers any active stingers to release more venom, so you want to delicately lift the tentacles off the skin.

Don’t rinse with water.

Fresh water can cause any active stingers to deploy, and salt water can spread the tentacles and stinging cells.

Don’t urinate on the sting.

This popular advice does not alleviate the sting and can make it worse. Urine is not acidic enough to deactivate the venom. Chemical compounds in urine may trigger undeployed stinging cells and spread the sting.

Don’t use lemon juice, garlic, athlete’s foot spray, head lice medicine, Epsom salts, bleach, gasoline or other so-called remedies.

WHAT EATS JELLYFISH?

Considering that jellyfish are composed of 95-99% water and possess stinging tentacles, they are on the menu for a surprising number of animals! The most nutritious parts of a jellyfish are the mesoglia and reproductive organs. Some animals will target these parts and avoid the rest. The most common predator of jellyfish are other jellyfish! Other jellyfish predators include several species of fish, birds, crabs and sea turtles.

Jellyfish are a major prey item for sea turtles, especially the leatherback sea turtle, Dermochelys coriacea. Jellyfish make up the majority of the leatherback’s diet, diving up to 4,000 ft deep hunting them.

Unfortunately, plastic bags closely resemble jellyfish in the water, which leads to animals accidentally ingesting them. This can be deadly, as the bags can get stuck in the animal’s digestive system or cause them to choke.

WHAT ARE THE MOST COMMON SPECIES OF JELLYFISH IN THE FLORIDA KEYS?

CASSIOPEA XAMACHANA

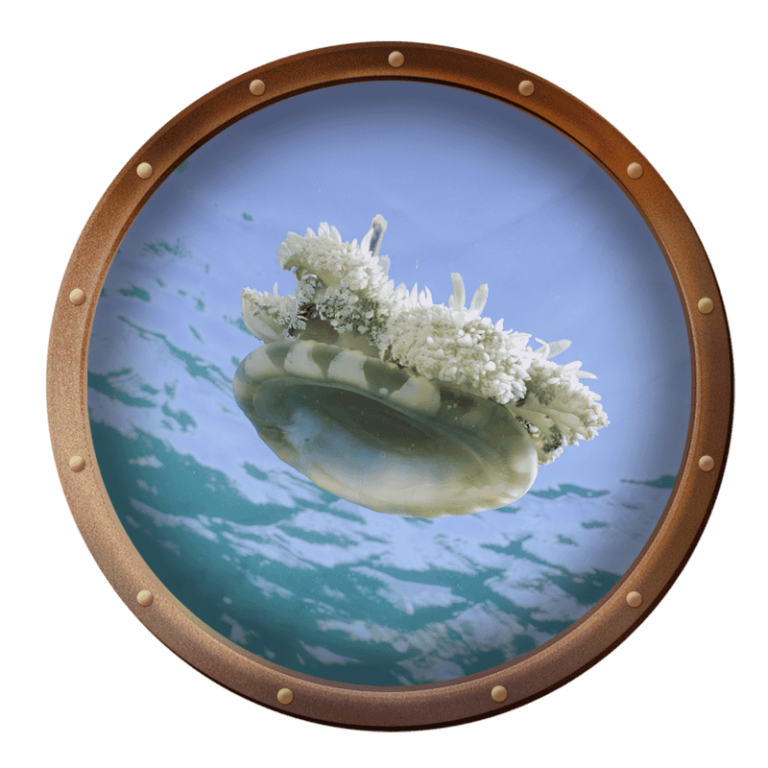

CASSIOPEA/UPSIDE-DOWN JELLYFISH

- Cassiopea, or upside-down jellyfish, are a common sight in the shallow seagrass and mangrove habitats around the Florida Keys. Take a kayak trip to see large “fields” of these animals resting on the bottom in the shallows.

- Cassiopea jellyfish spend most of their adult lives upside down on the seafloor, giving them their common name.

- These animals have photosynthetic algae that live in their bodies, which make food for the jellyfish and give them their colors.

- Cassiopea jellyfish are a cause of “stinging water” or “ghost stings.” These animals release mucus grenades filled with stinging cells called cassiosomes when disturbed.The cassiosomes float in the water column and sting small prey items that sink down to the jellyfish.

- These are also used for defense when the Cassiopea is disturbed, creating the “stinging water” that can irritate your skin!

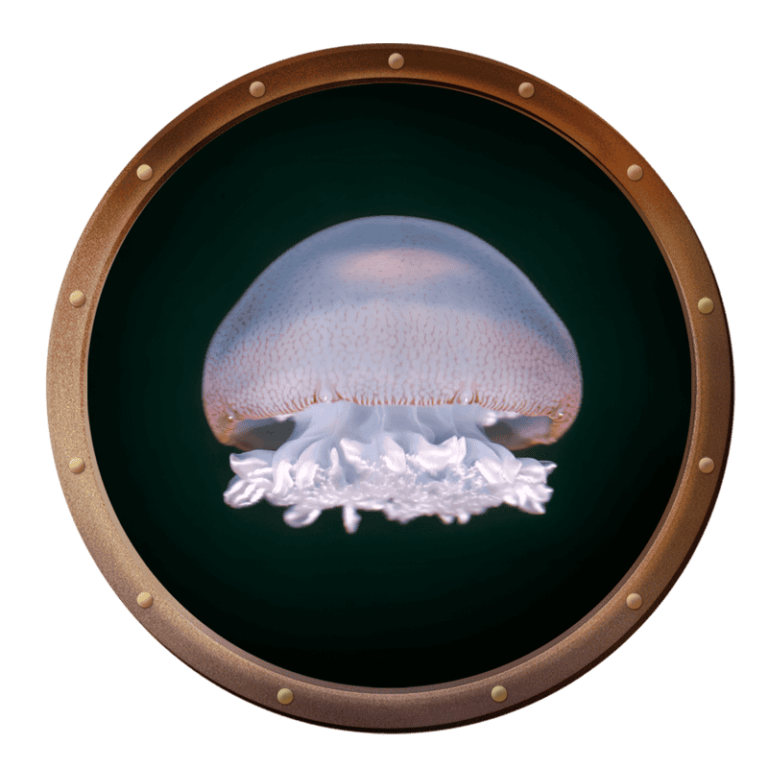

AURELIA AURITA

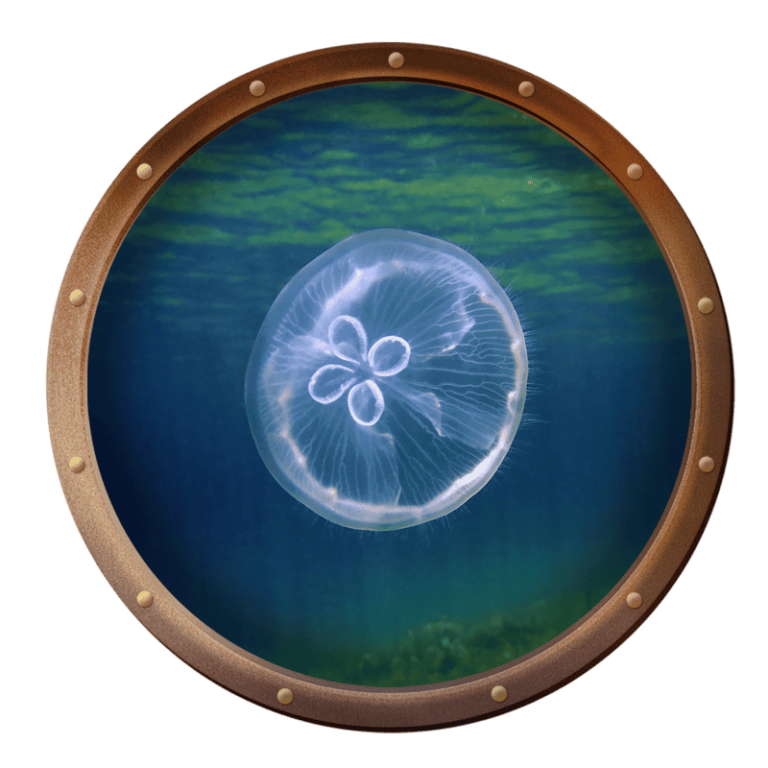

MOON JELLYFISH

- Moon jellyfish have a global distribution and are common in ocean waters between 43˚and 88˚F.

- This species is a predator but also an important food source for other animals, including sea turtles and the pink meanie jellyfish.

- The distinct clover shape visible through the bell is the gonads of this species.

- Moon jellyfish can appear clear to a light pink or purple color.

STOMOLOPHUS MELEAGRIS

CANNONBALL JELLYFISH

- The cannonball, or cabbage head, jellyfish, is the most common jellyfish species on the southeastern coast of the United States, especially during fall and summer.

- This species does not have a sting that is dangerous to humans, but it does produce a toxic mucus when disturbed. The toxin is harmful to small fish, discourages most predators, and can even cause cardiac symptoms in people.

- Cannonball jellyfish are a popular food item in Asia! Shrimp trawlers switch to fishing for these jellyfish in the off season. There is a high demand for dried cannonball jellyfish.

DRYMONEMA LARSONI

PINK MEANIE

- This species was discovered in the Gulf of Mexico in 2000. It was originally thought to be from the Mediterranean, but genetic studies have confirmed that it is not only a new species but an entirely new family of jellyfish!

- The pink meanie can get huge! The bell can reach 3 ft in diameter, and the stinging tentacles can stretch 100 ft. Some of the tentacles are arranged in a “curtain” held close to the bell.

- The pink meanie is jellyvorous, meaning it eats other jellyfish. It has been documented eating 34 jellyfish at one time!

PHYSALIA PHYSALIS

PORTUGUESE MAN O’ WAR

- The Portuguese man o’ war is not really a jellyfish! It is a close relative though, in the class Hydrozoa.

- It is not one individual! It is a siphonophore, made up of colonies of polyps that are genetic clones but perform different functions.

- There are four main types of polyps, or zooids:

- Pneumatophore-the gas filled float acts as a sail. The common name for this animal comes from the float’s resemblance to an 18th century Portuguese warship under full sail.

- Gastrozooids-feeding tentacles that digest food.

- Dactylozooids-contain powerful stinging cells for defense and capturing prey.

- Gonozooids-reproductive polyps

- The tentacles can extend 165 ft in the water!

CTENOPHORES

COMB JELLIES

- Comb jellies are not true jellyfish. In fact, they are from an entirely different phylum, Ctenophora!

- They may have been some of the first animals on earth, estimated to have appeared more than 700 million years ago, possibly even before sponges.

- The name for this group comes from the eight rows of pulsating cilia, called combs, lining the edges of the animal. The iridescent cilia pulse in coordinated waves to move the animal through the water and catch the light, making a shimmering rainbow display.

- Comb jellies do not sting. They lack stinging nematocysts but do have sticky colloblasts, which adhere to prey.

- Many comb jellies are bioluminescent. They produce a greenish-blue light when disturbed that can be observed at night.